home | paul barnett editorial | bibliography | the jg archive | store | paul's blog | links | places we like to visit | contact

| Perceptualistics: The Art of Jael |

|

by John Grant Jael is primarily known as an illustrator, but Perceptualistics focuses on her fine art, which I'm sure you'll agree, after looking at the sample pictures below (reproduced by kind permission of Jael), is stunning.

all's State Fair When I first got the inclination to do portraits I thought, 'Wow, this is a strange idea.' I had been drawing my children as babies - when they were sleeping I would sit there and draw them - and I knew I had a very good talent for likenesses. For whatever reason, when Sammy died and I realized how superficial I'd been being, the idea of doing portraits just popped into my head. It was like Joan of Arc hearing the voices.

Jael had been a professional performance artist throughout her childhood, and her creative aspirations had been taken seriously by those around her. Now, on the Kamas farm, as happens unintentionally to so many women who become wives and mothers, she was expected to be primarily a home-maker, with her art regarded as just a rather engaging hobby. One day she decided to do something about this. She went to the State Fair and booked herself space there as a portraitist for the next ten days; then came home and presented this to her husband as a fait accompli. When she turned up the first day with her easel and paints she discovered that, by lucky coincidence, the portraitist who'd worked the Fair for the past decade had for some reason decided to stop doing so. This was not quite such good news for Jael as one might expect, because she was uneasily aware that, whereas the customers assumed her to be a practised portraitist, in fact she was anything but. She had to learn fast. Her subjects, she rapidly discovered, were not just human: quite a number of sheep, prize rams, dogs, horses and so on were brought for her attentions, which involved hosing out the stall after each 'sitting'. Sometimes she was even asked to paint a peregrine falcon. Also, it being a State Fair and even though this was Utah, quite a number of her clients were drunk. One of them arrived at her stall at ten o'clock one night with 'an eye that was about five inches out from his face and was all black and blue and green'. It turned out he wanted to be painted exactly that way so he could give the portrait to the girlfriend who'd just dumped him, emphasizing her point with a punch in the eye. Charles Halford, whom I hadn't seen since I was about 15 and working as an apprentice in his ad agency, came by and saw me when I was set up for the second year doing my portraits. He didn't even say 'hello' to begin with, he just said: 'Your noses are flat.' He was right. At first I was really ticked at him, but then I realized he was definitely right. Even today I don't take criticism easily, but I do think about it later. Halford was to help her solve another problem connected with art and the State Fair. As well as painting portraits for the passing trade, Jael entered art for competition. One year she wanted to enter a 'very demure' painting of a nude. This was rejected on the grounds that it was 'frontal' - a rejection that infuriated her because one of the paintings accepted was of a woman bending over and provocatively thrusting a lovingly rendered rear end in the face of the viewer; that was regarded as OK because the rear end in question was bikini-clad. She went to the local Woolworths, bought herself a cheap paintbrush and paints, and, sitting outside on the steps of the exhibition building so that all could see her, quickly painted leaves over the offending areas. She then resubmitted the painting. The judges were not amused by what they regarded as insubordination.

The succeeding year she took her cue from a story Halford told her about what he'd done when the ladies of Springville, Utah, had insisted he enter a painting for competition even though he didn't have time to do anything. His solution to the problem had been to take one of his spare drawing boards, saw out a heavily paint-spattered rectangle, and frame it. The judges had been so impressed by this 'abstract' that they'd awarded it first prize. Following Halford's lead, Jael took a 5ft x 5ft (1.5m x 1.5m) square of plyboard, gave it an inch-deep frame - so the whole was rather like a tray - and, working not in a studio but in her farmhouse kitchen, filled the frame with putty, then searched around for some suitably artistic objets trouvÇs. Since the putty dried quickly, she had to trouve whatever was closest to hand, which was the contents of the kitchen drawers: a comb, a mirror fragment, bottle caps, pills, even a piece of stale toast . . . All of this and more she gleefully stuck into the putty. Once the putty had hardened, she looked at it 'and thought I couldn't just leave it that ugly beige-grey'. Accordingly, she took some tempera and painted her 'artwork' in a tasteful mix of lime-green and shocking pink: I entered it for the State Fair contest and won an Honourable Mention. This was when I knew for sure I would never be part of the ladies' artistic circle in Utah. There was a certain amount of hubbub among State Fair visitors

about some of the other art Jael was exhibiting: it was

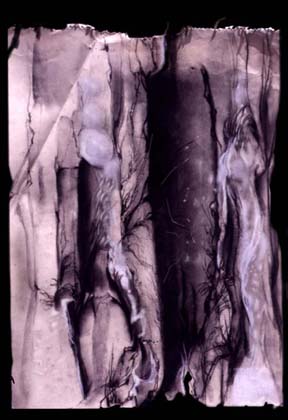

'controversial'. Her early mentor, Erla Young, looking at the

display each year, kept telling her she'd get nowhere in Utah

with such stuff. One day Jael came across a mother and daughter

discussing a painting she'd hung of a nude - she recalls it as

being rather like Dweller (see page 00 < Jael's own attitude is, obviously, exactly the opposite. She has always loved the human form: 'The body is like a landscape to me.' I think I learnt early to love it from Alvin Gittins during the time I studied under him. I recall one occasion when he took three of us into his own private studio, which was really tiny, and showed us a painting he'd done that was almost like Botticelli's Venus - the one of Venus on the clamshell. Gittins had done a nude portrait of a pregnant woman, close to her term. She had beautiful flowing red hair and her skin was so pale that it was almost iridescent. She was just standing there in the painting, full on. It was technically perfect - the flesh superbly rendered - but that wasn't what struck us: it was the living, breathing presence of her.

There had been other commercial outlets for her art. Long before, when she was about 15, her mother's friend Charles Halford owned a small ad agency, and took her on as an apprentice. She can remember evenings spent sitting in one of Utah's rare bars, painting to the background sound of Martin Denny & His Orchestra - Elvis and rock'n'roll were still a few years in the future. One job was to paint posters for the new movie 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Without access to offset printing, every poster had to be painted by hand; Jael can't recall how many times she painted this single poster, but says it felt like she did one for each league. Nevertheless, she loved the experience, just being left on her own to get on with it, the thrilling smell of the adjacent printing press in her nostrils. Now, years later, for a while she thought the family might have to rely entirely on the income from her public and commercial art - her husband had been badly burned in an accident, and there was a possibility he might be an invalid for life. Fortunately that proved not to be the case, but even so, as insurance, she took a teaching degree at the University of Utah. It was there that she had the opportunity to study under Alvin Gittins. This was not the first time the two had encountered each other. Years before, as a 15-year-old, Jael had watched him paint a portrait of her grandmother, then aged 93. The old woman was painted crocheting a little pink sweater that has since been handed down through generations of the children of Jael's family. She believes the experience of watching him at work and then seeing the final product - 'it was living and breathing' - was a major inspiration to her to plan a future career as an artist. But it wasn't just her nudes that were 'controversial' at the State Fair. Sometimes, both in Utah and later in Las Vegas, on the rare occasions when the demand for portraits eased off, she'd keep herself busy with a Perceptualistic painting. Often enough people would look at one of these and say, 'What is that?' It was a long time before Jael could find a suitable reply, and in the end she discovered it in a book about the painter Georgia O'Keefe - of whom Jael is a great fan. It is an unfortunate habit of those who look at art that they tend to tell the artist why she or he has done something. On once being told she'd painted a flower with a particular purpose in mind, O'Keefe snapped back that she had done no such thing: she had painted the flower for her own reasons; whatever the observer read into it was the observer's. Likewise with the Perceptualistics: for Jael, the painting of them is the telling of a story for herself; when each of us looks at one of them, we must tell our own story. leaving for Las Vegas 'I cherished that place,' Jael now says of the Kamas Valley farm, 'but then we lost it in a bankruptcy, which broke my heart. Things kind of went downhill with the marriage from that point on.' Divorce loomed. She taught high school for a while, making use of the degree she'd gained at the University of Utah.

After the divorce, she moved with the children to live in Las Vegas, Nevada, for seven years. It was, of course, a major cultural jolt: although she'd been a professional artist for over two decades by now, she had also been a farm wife and a mother, living in a conservative community; now she was thrust into the freewheeling glitz of Vegas. Although she established a position for herself painting in public, as at the State Fair, the environment could hardly have been more different: slap in the middle of a casino, between the slot machines and the crap tables. There was a security booth nearby, a proximity which from time to time proved useful. Initially she had a little apartment behind the MGM Grand; later she moved to another across the street from the Tropicana. She usually started work at about four in the afternoon and finished around one or two in the morning, having found that this schedule best fitted in with her children's school hours. Merina, the youngest, would sit with her after school as she worked and do her homework or otherwise occupy herself; today all of the children say that some of their fondest childhood memories are of sharpening Jael's pencils in all the different places where she painted while they were growing up. She got a lot of attention from the casino customers as she painted - partly because she 'dressed just a little provocatively because it was good for business, and only because the cocktail waitresses dressed about two hundred per cent more provocatively than I did', but mainly because of the paintings she was producing: portraits whenever anyone commissioned her - either in live sittings or, if the customers wanted to be portrayed in fantasticated settings, from photographs - and Perceptualistics in between times. 'All the drunks in the world' came to watch her at work. She recalls one saying to her, 'Shay, honey, can you draw me below the belt?' To the delight of twenty or thirty onlookers she replied sweetly: 'I'm sorry, sir, but I don't deal in microbiology.' She was good friends with a lot of the dancers along the Strip. In those days the community surrounding the Strip was actually a fairly safe one, and was not marked by lax morals. 'Outsiders might come along and drop someone down a manhole and you'd never see him again, but the community around the Strip was itself a conservative one - really straitlaced.' This was not always understood, even by those who lived in the area. Nearby was the Nellis Air Force Base, with Clark College not far from it; the college employed her to teach life-drawing, painting and creative painting, and it was only natural that she should recruit some of her dancer friends as models. The whole point of life-drawing is, of course, to work with the naked human form, but it was two full years before she was able to persuade the college authorities that the dancers were perfectly capable of posing nude without permanently corrupting either their own morals or those of the students - that it would all be in 'perfectly good taste'. Back in the casino, she was making good friends also with some of those who commissioned portraits from her: One day a woman's voice asked from behind me if I could do a portrait of her, and without turning around I said, 'Sure.' Then, when I turned to look at her I saw she had no face - quite literally. She had just a slit for a mouth and slits for the nostrils. Her eyes had no eyelids or eyebrows. My reaction must have shown, but she told me not to get nervous. She was there in Vegas with her eldest son, who was getting married. She didn't want to be part of a family photograph, for obvious reasons, but she did want to give something of herself to her son and his new wife. It turned out she'd been butchered by an incompetent surgeon trying to fix a cleft palate when she was four. The nerves had never developed so neither had her facial features - the skin had just tightened around her skull. In spite of all that, she'd married a really nice, good-looking guy and they'd had six children. And she had this wonderful warm personality and sense of humour. By the time we'd finished the live sitting for her portrait, everyone gathered around was in tears about her story. Not all the experiences were so happy. Two of the hotel employees asked her to paint a joint portrait of them, and then kept on never quite getting around to paying for it. Her attitude was that, until they paid, they didn't get the portrait - but she kept it up on prominent display in her booth, and every now and then one or other of the pair would come to look at it and do a bit of preening. Finally she got so angry with them that one of them was provoked into offering her a fight. 'Try it,' she said firmly. Although she's an extremely small woman, he had better sense. Finally she complained to the hotel's personnel department about the lack of payment, and the defaulting couple were forced to stump up. A considerable advantage of the casino over the State Fair was that children - her own excepted - were not allowed in, 'so I was free of all the little rugrats that used to bother me all those years'. Instead, though, she had to cope with the ubiquitous presence of the Mafia. This was not altogether a bad thing: one of the reasons Las Vegas was so law-abiding (as it were) in those days was that the Mafia tended to police it with, if necessary, a fairly draconian hand. But it did give her some uneasy moments: If you ever find me in cement you'll know I shouldn't have told this story . . . They had a big yacht actually inside the casino, just opposite where I was working, on the other side of the slot machines but still close enough for me to be able to hear people talking in there. One night I heard whispered conversation and realized this was a group of Mafia people - very obviously some of the godfathers. They were talking about stuff I certainly shouldn't have overheard. I was literally praying they wouldn't look across and see that I was overhearing them. I just stayed very, very, very busy with my work. But even the godfathers couldn't control the forces of nature. Vegas is famous for its flash floods, which come pouring down out of the surrounding hills. One day a bunch of people came charging in to where Jael was painting and told her there was something she must see outside. A flash flood at Caesar's Palace had swept the five or six hundred top-of-the-range cars - the apples of the Mafia bosses' hearts - out of the parking lot there and into an adjacent underpass, along with a mountain of mud and debris. As she watched, three forlorn-looking cranes started trying to salvage what they could from this shambles. The cars' owners, high rollers just a few hours before but now reduced to the same level as the rest of humanity, were watching in impotent misery, fully aware that their magnificent machines were certain to emerge from the sludge as total writeoffs. Aside from the people she met and the fun she often had, what affected her most about Vegas was the desert around it, which she adored: It gave me many . . . moods. Sometimes I'd go out there with friends at two o'clock in the morning and fly kites. It was lovely and warm in the desert at that hour, with just a whisper of a breeze. With other friends I used to go out on a boat overnight and then, just at the break of dawn, start water- skiing. The water would be like glass, and there'd be crows flying overhead - always made me think of Carlos Castaneda! Perhaps my favourite feeling came when I went out to the Valley of Fire at twilight and watched the swimming, iridescent colours of the desert - so stark and so strange and so alien. the lure of the West In due course Vegas palled, and she began to look around for somewhere else to take herself. By now the children were graduating and moving out into the wider world. Her eldest child, Catherine, had joined the US Army. Her elder son, Daniel, was just getting married, and his younger brother, Justin, had joined the Air Force. The youngest, Merina, went back to live with Jael's ex-husband for a couple of years. She was once again a single, unencumbered woman - and determined to stay that way: in her marriage she'd unwittingly grown accustomed to playing a subservient role to everyone else around her, and she had no wish to return to that state. Her eye fell upon California, and in particular upon Santa Cruz. At the time Santa Cruz was something of a creative cradle: in or near the city dwelt such luminaries as Jerry Garcia, the Doobie Brothers - the Doobies' Tiran Porter used to play with the jazz band upstairs from Jael's studio at the bottom of the Cooper House in Santa Cruz - the Smothers Brothers and Carlos Santana. She was even able to play a bit part in a Clint Eastwood movie, Sudden Impact (1983): All you see of me is a flash of blue and red, but it was great fun and I got paid as an extra. I was set up painting on the sidewalk during the scene where the bad guy on a motorbike is being chased by Eastwood in a retirement van. I'd actually begged to put my artwork in the most vulnerable position so that, if it got damaged when the motorbike crashed, I'd get paid for that as well.

Because of the cultural ambience, she had to undergo a change of style. In Vegas she'd delighted in dressing in hippy uniform - long skirts, little halters, floppy hats - because it contrasted so pleasingly with the typically formal attire of her clients. Here in Santa Cruz, however, there were lots of hippies, some of whom constituted something of a problem because of their incessant panhandling. Eager to contrast yet again, she had to dig out her Levis . . . Soon her reputation - for her art, not her costume - spread up and down the coast around Santa Cruz. Her Perceptualistics were the object of especial attention and enthusiasm: even though, as always, she was painting them for her own benefit and hers alone, they always found an eager market. She received commissions, including a few album covers, 'not for any really major bands, but they were major enough to be making albums'. As with Las Vegas, what she remembers most about her years in Santa Cruz is the scenery. Vegas had offered her the desert; the most notable features of Santa Cruz's surrounds were the shores and seascapes. Both these contrasting scenic regimes contributed immeasurably, she believes, to her Perceptualistics: 'In fact, you could almost say that it was from here that the Perceptualistics came.' A favourite occupation was to drive alone to the ocean - still her love of solitude expressed itself - and walk along to one of the hundreds of coves, then sit right at the edge and watch through the muffling fog as the sailboats, mainly from San Francisco, silently crossed Monterey Bay. 'They were like ghosts coming silently into harbour through the mist.' And then there were the pelicans, swooping down in majestic formation to skim across the water, seizing unwary fish. At nights she often went fishing with friends and watched the seals teaching their pups how to rob the crabbing nets. All through my life the important thing for me has never been the actual location where I'm living but the landscape around me - the things that I can find in nature. My art is not an entertainment: it is an attempt to encapsulate the feeling that we are at one with the universe. If we could only see that we are not separate, but a part of what is around us - not just of the landscape but of the cosmic landscape. We're part of the cosmic soup. In Santa Cruz, while not exposed to the full glare of the casino, she was still painting in the public eye. Although she had been doing this for years, both at the Utah State Fair and in Vegas, she had come to love it no better. While the vast majority of the people who came to watch her were sensitive, some were less so. At the time she was painting Perceptualistics as her 'escapes': they offered her a portal through which she could go to find somewhere other than the present. As noted, the Perceptualistics were much appreciated by the locals, but occasionally she'd find herself confronted by someone less astute. 'Oh, are you doing this?' they might ask, to which she'd respond tartly: 'No, I hire elves to do it for me.' Responses to other, similar questions could be equally acid if it was a bad day. She was growing increasingly tired of such remarks and of being in public so much: 'I knew I had to find my artist's garret somewhere.' But for a long time that was something to be dealt with tomorrow. She recalls an occasion when she was painting a Perceptualistic and a group of visitors asked her: 'What is it?' Taking a leaf out of Georgia O'Keefe's book, she politely (it must have been a good day) replied: 'Whatever you want to see in it is your pleasure.' This response didn't satisfy them, and they continued to debate the matter for a while before finally departing. The exchange had been overheard by Jael's boyfriend of the time, Daniel Conn, and after they'd gone he said to her: 'You know what? Most people need a banana in the middle of a picture. They're not comfortable unless they can see that banana. If they can't see a banana, it annoys them that they have to sit there and figure it out . . .' This observation continues to have a profound effect on Jael's thinking, not just about visual art but about all creative activities: Why do we have to have the banana in the middle? Why do we have to have something that's obvious? Why do we have to spell it out? Why not let the viewers use their imaginations to take that leap of faith to where they want to go? The course of her life was changed immeasurably through a chance sighting of a flyer advertising a symposium to be held in Santa Cruz. Called Contact, this symposium was to be an exercise in theoretical world-building. She might not have paid it much attention had she not noticed that among the principal guests were Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle: 'I was really fond of Larry Niven's Ringworld and others, as was my brother Ted, and so I decided I had to go.' Aware that she was a complete tyro so far as the subject matter was concerned, she sat right at the back as the speakers did their stuff. It seems in fact to have been a lecture by Richard Leakey that persuaded her she had to play a more active role in what she discovered was to be an annual event. What she liked about Contact was that it was a professional gathering, rather than fan-based, as are science- fiction conventions. (She knew very little about sf conventions at the time. In due course she dipped her toes in the water by going to a Westercon - the annual sf/fantasy convention held up and down the West Coast of the USA and Canada. She was mightily impressed by the extravagance of the costumes in the Masquerade.) At the following year's Contact she did indeed play a more active part (in due course she would become a member of Contact's Board of Directors), offering instant visualizations of the environments the theoreticians were conjuring up. In the course of this she got to know Niven and Pournelle much better. When she mentioned in conversation that she had always dreamed of doing covers for science-fiction and fantasy books, they advised her that her only option was to go East, to New York, which was where the illustration jobs were. She wasn't quite ready for such a drastic shift in her lifestyle, but she did agree to make an exploratory foray to Manhattan, armed with a recommendation from Pournelle to publisher Jim Baen: When I flew on my preliminary trip out to New York with my boxful of art to show people, the Statue of Liberty was in scaffolding. Even so, it was like my Mount Everest. I was actually in tears, because in a way I was fulfilling a dream that should have been my mom's to complete. It was such an adventure for me - this person from the West Coast coming to the big exciting city. It was quite a while before I realized that the people I was meeting in New York were amazed by all the things I had done. One of the most enchanting evenings during that trip was on a day when I'd seen three publishers. I was walking with all my things up Park Avenue, after having come through the tunnel at Grand Central. It was twilight, and as I looked to either side of me the lights were reflecting off the green glass of the skyscrapers. I wanted to stop all these people who were in such a hurry, rushing to catch their trains or whatever, and tell them, 'Do you know how beautiful this street is?' I kept on walking and took the turn to get to Central Park, and all the while I was thinking to myself what a fulfilment this was. I was just about to walk into the park when I realized that it was maybe not such a good idea, so instead I bought myself a Dove Bar and ate it listening to the music that was playing in the Plaza. I was by myself, of course, just the way I wanted to be. It was a marvellous way to end an enchanted evening. The first book cover she did, working in her garage, was for Alan Hruska's novel Borrowed Time. 'I didn't really know what I was doing, but I got local people in Santa Cruz to pose for me.' At last, one night, she finished the painting. She had done it in oils, but nevertheless she was optimistic that the paint would have dried sufficiently for her to be able to ship the artwork to Jim Baen the following morning. She took a short break to celebrate the completion of the commission, then went back to the garage to see how the paint was drying. To her horror she discovered that hundreds of tiny grey moths had settled on the wet paint and stuck there. Cue for a major panic. She could hardly just paint over the bumps, some of which were still fitfully moving; and neither, she thought, could she simply brush them off, because they'd leave smears. In the end, though, she had to opt for the latter course, then stay up all night painting over the smears. Afterwards she put a fan on the picture until the oils were finally dry enough for it to be shipped. It was all part of the learning experience, of course, and it left her with a recurring dream that she suffered for some weeks thereafter. In this dream she was working on this same painting when a single giant moth landed on it. The moth then flapped itself airborne and flew away, with the whole of her painting stuck to it, so that she was left in front of a blank canvas. It was no secret in the small artistic community of Santa Cruz that Jael had started to get cover commissions. She was hunting around for models locally - 'I went up and down the streets looking for a black Othello type for Robert Silverberg's Shadrach in the Furnace, my second cover' - and even without this she was so excited by the new development in her life that she had to tell everybody about it. And by now other voices were adding to Niven's and Pournelle's chorus urging her to look to New York for her future life. Prominent among such advocates were Vincent Di Fate and Kennedy Poyser, who spent hours on the phone to her while she was still in Santa Cruz doing her first two covers.

In the end she decided on a compromise. She would move to New York for a couple of years and then, having discovered fame and fortune there, return to Santa Cruz to continue working for the New York publishers from this West Coast base. She must have realized at the time that such compromises sound great in theory but never quite work out in practice, and certainly the people around her did. Her colleagues in Contact were obviously very sad to lose her, but so were her many friends; although she does not believe herself to be a very gregarious person, she has in fact a seemingly infinite capacity for forming friendships wherever she goes. But she'd made her decision; now all that had to be done was to put it into effect. The friends I'd had in Las Vegas told me I couldn't leave, but I did, to go to Santa Cruz. The people in Santa Cruz told me I couldn't leave, but I did - although this time it was harder. The End Copyright © , John Grant |